Over the past three decades, lawmakers have increasingly turned to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) to deliver social and economic benefits through the tax code rather than traditional federal agencies. As a result, the IRS now administers 21 refundable and non-refundable taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. credits for individuals, such as the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and Child Tax Credit (CTC), and roughly two dozen more tax breaks for corporations, such as the green energy tax credits enacted in the Inflation Reduction Act.

Because tax credits do not have the same built-in metrics and accountability that typically accompany formal spending programs, little is known about the efficacy of these tax programs. IRS data can tell us how many taxpayers claimed a tax creditA tax credit is a provision that reduces a taxpayer’s final tax bill, dollar-for-dollar. A tax credit differs from deductions and exemptions, which reduce taxable income, rather than the taxpayer’s tax bill directly. and how much it reduced their tax liability but cannot tell us if the credit changed taxpayer behavior or decision-making. However, the IRS is required to estimate the amount of “improper payments” of refundable tax creditA refundable tax credit can be used to generate a federal tax refund larger than the amount of tax paid throughout the year. In other words, a refundable tax credit creates the possibility of a negative federal tax liability. An example of a refundable tax credit is the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). programs. Overpayments result from taxpayer errors, confusion, or outright fraud and have become endemic to these programs.

Tax credits reduce a taxpayer’s tax liability dollar-for-dollar and refundable tax credits are paid out when a taxpayer’s tax liability is reduced to zero. For example, if a taxpayer with one child is eligible for a $2,000 credit but owes only $1,000 in taxes, half of the credit would erase her tax liability and she would receive the remaining $1,000 as a direct payment from the IRS.

In 2022, 27 percent of refundable tax credits were overpayments. In 2022, the IRS paid out $98 billion in refundable tax credits to four programs: the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), Additional Child Tax Credit (ACTC), American Opportunity Tax Credit (AOTC), and the Net Premium Tax Credit (Net PTC). Recent reports by the Government Accountability Office (GAO) and the IRS’s Inspector General for Tax Administration (TIGTA) estimate that $26 billion in refundable tax credits were overpayments.

| Total Refundable Payments (in Billions) | Estimated Overpayments (in Billions) | Estimated Overpayment Rate | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) | $57.50 | $18.20 | 32% |

| Additional Child Tax Credit (ACTC) | $32.80 | $5.20 | 16% |

| American Opportunity Tax Credit (AOTC) | $5.60 | $2.00 | 36% |

| Net Premium Tax Credit (Net PTC) | $2.10 | $0.60 | 24% |

| Overall Totals and Average Overpayment Rate | $98.00 | $26.00 | 27% |

|

Source: PaymentAccuracy.gov, https://www.cfo.gov/wp-content-2/uploads/2022/FY2022%20Payment%20Accuracy%20Dataset_Data_As_Of_11_16_2022_Updated.xlsx |

|||

But the IRS and Treasury claim that overpayments are not the result of bad management or poor internal control issues. Instead, the IRS claims that overpayments are the result of factors beyond its control, such as the “statutory design of the RTCs, reliance on taxpayers’ self-certification of the accuracy of their returns, and the lack of third-party data for verification.”

They may be right. And they may also have identified the fatal flaw in trying to deliver social and economic benefits through the tax code.

The EITC, which is intended to supplement the income of the working poor, accounted for the largest overpayments. As the nearby table illustrates, nearly $1 of every $3 in EITC refundable payments was erroneous in 2022, amounting to $18 billion out of the $57.5 billion in EITC refund payments.

The EITC has a long history of erroneous overpayments. Indeed, based on the data available on PaymentAccuracy.gov, between 2004 and 2022, the EITC error rate averaged 25 percent. After adjusting for inflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power. , EITC overpayments totaled $351 billion over that 18-year period.

The ACTC had $5.2 billion in overpayments in 2022. Out of the nearly $33 billion in refundable CTCs paid out in 2022, 16 percent were overpayments. According to PaymentAccuracy.gov, since 2019, ACTC overpayments have averaged nearly 14 percent and totaled $22 billion.

In 2022, the AOTC had the highest overpayment rate at 36 percent. The AOTC is intended to reduce the costs of higher education but, like the EITC, has a long history of erroneous payments. Indeed, the TIGTA estimated that in 2012, “more than 3.6 million taxpayers (claiming more than 3.8 million students) received more than $5.6 billion in potentially erroneous education credits ($2.5 billion in refundable credits and $3.1 billion in nonrefundable credits).”

The $2 billion in overpayments in 2022 represent only the errors in the refundable portion of the AOTC. The IRS does not report the error rate of the nonrefundable portion.

Lastly, the net PTC is the refundable portion of the tax subsidies for the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, also known as Obamacare. The IRS co-manages the PTC with the Department of Health and Human Services. Although the net subsidy is relatively small, just $2.1 billion, it did have an unusually high overpayment rate of 24 percent.

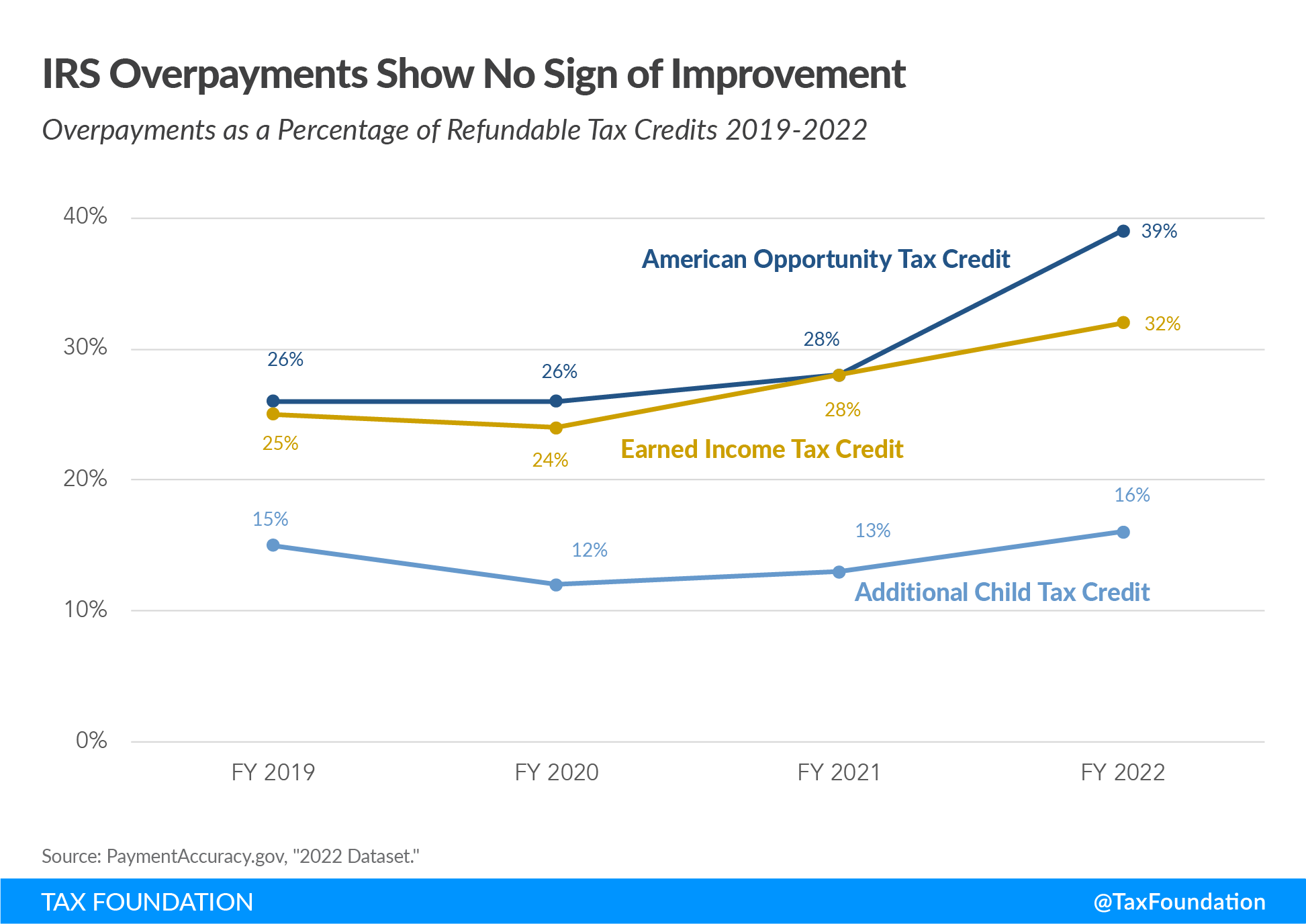

Despite the IRS’s best efforts, overpayments have increased recently, not declined. Indeed, the nearby chart illustrates the increasing overpayments in the three largest refundable tax credit programs since 2019. AOTC overpayments have increased the most, from 26 percent to 39 percent, while EITC overpayments increased from 25 percent to 32 percent after a slight dip in 2020. In 2019, the overpayment rate in the ACTC stood at 15 percent. The overpayment rate dropped in 2020 and 2021 before rising to 16 percent in 2022.

Why can’t the IRS prevent overpayments? The IRS claims that overpayments are caused by factors beyond its control. In many respects the agency is correct. Unlike most federal benefit programs, the IRS cannot control in advance who claims the benefit. Traditional social benefit programs such as Medicaid, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) require a lengthy application process and involve case workers who interview and pre-screen applicants to validate their eligibility.

Not so with tax credits and deductions. Tax benefits are self-validating. In other words, it is up to the taxpayer (or their preparer or software) to determine their eligibility for the tax break. The only method by which the IRS can verify eligibility for a refund is after the tax return has been submitted. Only then can the IRS check a return’s accuracy with costly enforcement tools, such as computer software, or through an auditA tax audit is when the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) conducts a formal investigation of financial information to verify an individual or corporation has accurately reported and paid their taxes. Selection can be at random, or due to unusual deductions or income reported on a tax return. .

The IRS claims that it does not have access to the kinds of third-party information that it would need to validate the different family arrangements and other circumstances that can cause errors, mistakes, or fraud in both the EITC and CTC programs. Treasury’s 2022 Annual Financial Report says that were the IRS to have access to such information, it would be intrusive while only yielding a marginal benefit relative to the cost.

The IRS says it can’t meet the Office of Management and Budget’s requirement to get overpayment error rates below 10 percent. Treasury says the IRS would need $2.5 billion in extra funds to audit 4.2 million EITC returns before allowing the refund to be paid.

Treasury admits that such an effort is a non-starter. Indeed, they understand that the high audit rates for the EITC in particular is a public relations problem. “The IRS allocates a disproportionate amount of enforcement resources to audit returns that claim one or more RTCs. This creates problems. Because lower-income taxpayers make up the majority of those claiming RTCs, they are subject to a disproportionate number of audits (RTC claimants are audited about three times the rate of other taxpayers).” Which, they acknowledge, “can lead to a negative perception of the IRS’s treatment of taxpayers.”

According to Treasury, total tax credits account for 15 percent of the individual income taxAn individual income tax (or personal income tax) is levied on the wages, salaries, investments, or other forms of income an individual or household earns. The U.S. imposes a progressive income tax where rates increase with income. The Federal Income Tax was established in 1913 with the ratification of the 16th Amendment. Though barely 100 years old, individual income taxes are the largest source of tax revenue in the U.S. underreporting tax gap. The EITC alone constitutes 10 percent of the tax gapThe tax gap is the difference between taxes legally owed and taxes collected. The gross tax gap in the U.S. accounts for at least 1 billion in lost revenue each year, according to the latest estimate by the IRS (2011 to 2013), suggesting a voluntary taxpayer compliance rate of 83.6 percent. The net tax gap is calculated by subtracting late tax collections from the gross tax gap: from 2011 to 2013, the average net gap was around 1 billion. . However, Treasury seems to imply that we may have to live with overpayments, saying that if the IRS were forced to put more audit resources into refundable tax credit returns, it would result in “a substantial loss in enforcement revenue, estimated at $6.4 billion…because the IRS would have to divert resources from programs with higher returns and tax gap elements to audits of RTC returns.”

Other design issues also cause confusion for taxpayers and administrative problems for the IRS. For example, each of these refundable tax credits has different income definitions, different rules for different family arrangements, residency requirements, and other conformity issues that leave the programs open to mistakes and abuse.

Treasury also blames paid preparers for contributing to the errors—or fraud. More than 50 percent of taxpayers claiming the EITC use paid preparers to complete their returns. Many are unenrolled return preparers, which the IRS says are often less qualified to manage complex returns such as the EITC.

The IRS has been set up for failure. Like a police officer who arrives at the scene after an alleged crime has been committed, the IRS is in a no-win situation because of the inherent design of tax credits. Since the IRS cannot pre-screen taxpayers before they take advantage of the programs, its only recourse for verifying the accuracy of a claim is through the heavy hand of audits or complex computer algorithms after the fact.

Lawmakers have made the situation worse by creating programs with complicated eligibility requirements that confuse taxpayers and raise administrative costs for the IRS. Lastly, tax programs do not have built-in metrics or measurable objectives, so the IRS is unable to measure their effectiveness.

These factors confirm why lawmakers should avoid delivering social and economic benefits through the tax code whenever possible and work to simplify or repeal the tax expenditures already in the tax code.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Subscribe