The Joint Committee on Taxation’s (JCT) December 2023 tax expenditureTax expenditures are a departure from the “normal” tax code that lower the tax burden of individuals or businesses, through an exemption, deduction, credit, or preferential rate. Expenditures can result in significant revenue losses to the government and include provisions such as the earned income tax credit (EITC), child tax credit (CTC), deduction for employer health-care contributions, and tax-advantaged savings plans. report shows a concerning trend in corporate taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. policy. The report shows the impact of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) and the 2022 InflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power. Reduction Act (IRA), with one effect particularly clear: corporate tax breaks have shifted away from deductions for general investment toward subsidies for specific types of investment.

Tax expenditures are policies that diverge from “normal” income taxation. However, what constitutes a normal income tax is controversial. The JCT report relies on the Haig-Simons definition of income, which defines income as consumption plus change in net worth. Consider how this affects the “normal” tax treatment of investment. When a company buys a new factory, its net worth does not immediately change. However, its net worth does decline as a factory depreciates (i.e., loses value over time), so under Haig-Simons, companies should take deductions for investments as an asset depreciates. Accordingly, deductions for investments in excess of economic depreciationDepreciation is a measurement of the “useful life” of a business asset, such as machinery or a factory, to determine the multiyear period over which the cost of that asset can be deducted from taxable income. Instead of allowing businesses to deduct the cost of investments immediately (i.e., full expensing), depreciation requires deductions to be taken over time, reducing their value and discouraging investment. count as tax expenditures under the JCT’s definitions.

The depreciation approach, however, is not economically sound. Spreading deductions for investments out over time means they lose value in real terms, thanks to inflation and opportunity cost. As a result, using economic depreciation in the tax system creates penalties for capital investment, which reduces investment and economic growth. The alternative to the Haig-Simons-style corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. is a cash flow-based corporate income tax, where companies deduct all costs (whether recurring operational expenses or major capital investments) immediately.

Because of a reliance on the Haig-Simons definition, the bottom-line totals of the JCT tax expenditures report do not distinguish between true subsidies (policies that provide additional support to businesses [e.g., an investment tax creditA tax credit is a provision that reduces a taxpayer’s final tax bill, dollar-for-dollar. A tax credit differs from deductions and exemptions, which reduce taxable income, rather than the taxpayer’s tax bill directly. ]) and deductions for investment costs incurred that would be normal under a cash flow tax. Nevertheless, when digging deeper into the report, one can see how the two types of policies have moved in different directions.

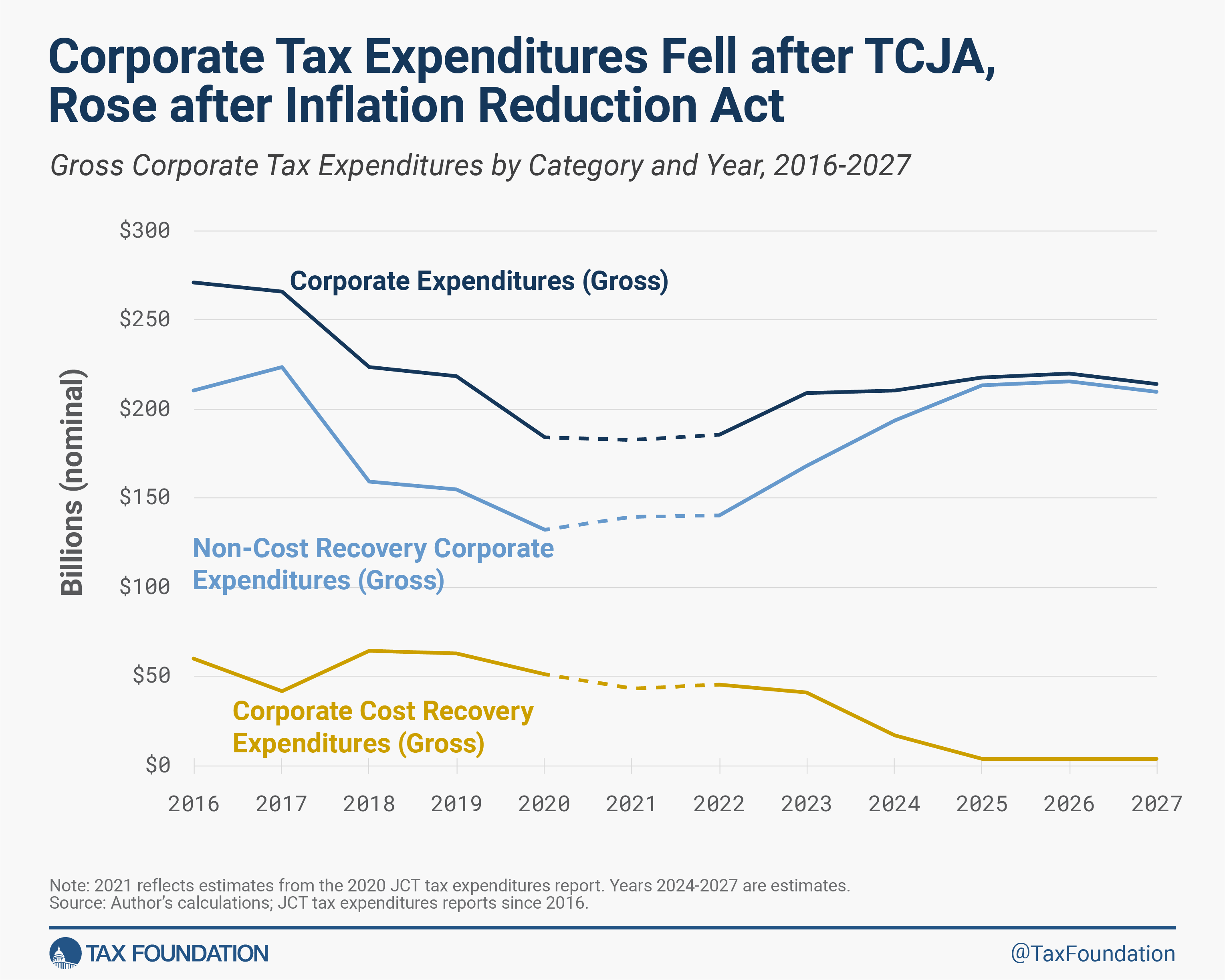

Overall, corporate tax expenditures fell substantially following the passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act in 2017. The drop mostly reflects the law’s reduction of the corporate tax rate—tax deductions are more valuable against a 35 percent corporate tax rate than they are against a 21 percent tax rate. However, the law did eliminate a major corporate tax expenditure, the 9 percent deduction for domestic production activities. At the same time, the TCJA introduced 100 percent bonus depreciationBonus depreciation allows firms to deduct a larger portion of certain “short-lived” investments in new or improved technology, equipment, or buildings in the first year. Allowing businesses to write off more investments partially alleviates a bias in the tax code and incentivizes companies to invest more, which, in the long run, raises worker productivity, boosts wages, and creates more jobs. for equipment and machinery, growing cost recoveryCost recovery is the ability of businesses to recover (deduct) the costs of their investments. It plays an important role in defining a business’ tax base and can impact investment decisions. When businesses cannot fully deduct capital expenditures, they spend less on capital, which reduces worker’s productivity and wages. tax expenditures.

The trend of higher cost recovery deductions and overall lower corporate tax expenditures—which generally reflects a move toward better tax policy—has begun to reverse. The TCJA replaced expensing for research and development (R&D) investment with amortization of R&D expenses at the beginning of 2022, and 100 percent bonus depreciation began phasing out at the beginning of 2023 (first to 80 percent, then it will drop by 20 percentage points each subsequent year). The TCJA phaseouts explain the decline in cost recovery tax expenditures since 2022.

The decline in total corporate tax expenditures has reversed in recent years thanks to the IRA and the CHIPS and Science Act, both enacted in 2022. While cost recovery expenditures have shrunk, expanded tax credits for renewable energy production, renewable energy investment, and advanced manufacturing have increased non-cost recovery expenditures enough to push up total expenditures. This reversal points to a troubling trend of moving away from the neutral tax treatment of investment toward targeted, industry-specific tax subsidies.

Table 1. Corporate Tax Expenditures for Energy Industry and Semiconductors versus Investment in Short-Lived Assets, 2016-2027

| 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | 2026 | 2027 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy (All Corporate Tax Expenditures)* | $9.3 | $9.6 | $10.4 | $10.3 | $12.8 | $12.7 | $10.1 | $23 | $42.8 | $61.1 | $71.5 | $73.8 |

| Accelerated Depreciation for Equipment in Excess of Alternative Depreciation System (ADS)** | $17.3 | $25.2 | $48.2 | $52.7 | $43.2 | $35.6 | $39.8 | $37.3 | $12.8 | -$6 | -$17.2 | -$24.6 |

Source: Author’s calculations; JCT tax expenditures reports since 2016.

*Includes some minor provisions (such as expensing for oil and gas exploration and development costs) that are not true subsidies.

**The negative numbers from 2025 to 2027 are a timing issue. The tax treatment of equipment will move toward matching ADS but will not become substantially worse than ADS as the negative numbers imply.

While the CHIPS Act and the IRA are aimed at legitimate policy goals—such as strategic competition with China and reducing greenhouse gas emissions, respectively—lawmakers should prioritize creating a tax system that supports investment more broadly rather than subsidizing specific industries and allowing broad, neutral pro-investment provisions to expire.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Subscribe